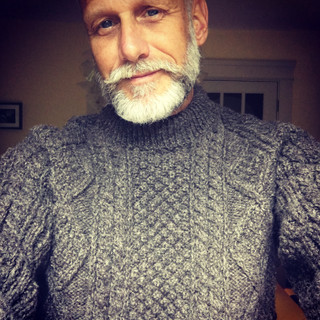

Introduction to Inferno: Una Selva Oscura

- Robert Brinkerhoff

- Jan 7, 2024

- 4 min read

Introduction to Inferno: Una Selva Oscura

Ink on paper. 2016

22 x 15”

In the opening canto of L’ Inferno, Dante finds himself in a dark wood (una selva oscura) having lost his way in life, both morally and intellectually. Thus begins the journey to Hell, Purgatory and Paradise, before returning to life a saved man.

* * *

For a couple of years, I taught a class with a brilliant RISD colleague—Mark Sherman, a medievalist in the Literary Arts and Studies Department. I learned a great deal from our experience, and particularly from Mark, who was not only a knowledgeable scholar but also a perfectly competent critic of visual communication. The class, "Illustrating Dante's Comedy," encouraged deeper reflection on the poem in its entirety, with the challenging premise of total immersion in both scholarly and studio investigation. We met for eight hours each week and talked constantly about the poem, its metaphorical and historical richness and how best to visualize it. I do think it was important for most of the students, as their apprehension of the content—written 700 years ago—was made more meaningful by their attempts at illustrating it, while their literary interpretation deepened their relationship to the content as artists. This was the goal, realized with exactitude through a huge investment of sweat and brain work.

It affected me too, and I remain grateful to Mark for resurrecting the poem for me. I don't think that any other teaching experience—at RISD or elsewhere—has more strongly influenced my own creative trajectory. I began by sketching in class as we discussed the poem and these little drawings eventually took shape as a project that's been consuming my attention for the past several months. Most of us read L'Inferno in high school or freshman lit classes in college, and its pulpy, phantasmal imagery appeals universally to youthful sensibilities. I last encountered L'Inferno (sans the rest of the poem) at age 19, my mind mired in newfound pleasures of freely available sex and beer and (finally, after 12 years of public school in which art class was shoved to the periphery) full-time dedication to art making. But in middle age I suspect the poem resonates more profoundly as it mirrors the preoccupations of people (like myself) whose paths in life are pondered with affection, regret, lost love, resentment and a desire to clarify, once and for all, the rest of the journey. Pick up Dante at age 50 and it will be a different literary experience. Spend many hours translating and drawing its tercets of terza rima and you'll realize how much you have in common with a 14th century poet, despite the hundreds of years and linguistic traditions that separate you.

I'm on sabbatical from teaching Illustration at RISD. My proposal, which was submitted in earnest many months ago, boldly (and with naive, puppy-dog enthusiasm, I will admit it) involved completion of 100 drawings based on La Commedia, an ambitious undertaking, to say the least. I've knocked a dent in it but I have a long way to go, of course. I still have time, and—as I near the ninth circle of hell in my efforts to illustrate this huge masterpiece—I'm probably about as intimidated as our hero was just before he encountered Lucifer, embedded in ice and chomping away on three sinners.

Recently (and I'm surprised that I never bothered to research this before) I took a look at relevant dates for the poem's creation. It took Dante, politically and socially exiled from Florence and couch surfing in other Italian cities, twelve years to complete the poem—from 1308-1320. He was, during its creation, between the ages of 43-and 55 years old. Coincidentally (or perhaps not) at age 43 I came out to my kids, friends and colleagues after almost 20 years of marriage to a beautiful, wise and forgiving woman and found myself in a dark wood: una selva oscura. Desperate for jarring change and a fresh start, I moved to Rome to teach for RISD and enjoyed the departure from routine for two transformative years. This was certainly a momentous turning point in life and the beginning of a period of introspection and self-awareness that has culminated in innumerable life changes. During the past eleven years I have experienced a protracted awakening. I stopped drinking. I enjoyed a seven-year relationship with a man I met in Rome. I became vegetarian. I tried to steer my kids from harm as they teetered on the cusp of adulthood. I lost my mother, a beautiful force of nature, who passed away a month ago at age 96. I looked back on the countless mistakes and losses I experienced along the way. I became a more courageous man.

I'm not presumptuous enough to liken my own artistic pursuits to those of Dante, but I've been awed by the richness of experience this project has afforded me. I have undertaken it analogously, approaching each canto, from beginning to end, in the proper sequence. Like Dante, I begin in the dark wood, wondering how the hell I got here, grateful for so much but cursing myself for squandering some unusual gifts. The project has been deliberately structured as time-consuming (and occasionally maddening, especially when my own lack of resourcefulness or other obstacles slow me down). And, more than any other aspect of learning it has afforded me, I have been allowed to study my own processes—intellectual, formal and technical—and this is precisely what the gift of sabbatical is about.

I'm including below the opening lines to L'Inferno, no doubt mirroring the experience of many of my brothers and sisters in mid-life, along with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1867 translation:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

ché la diritta via era smarrita.

—

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Comments